Why most first drafts of new plays are overwritten.

We get a lot of new plays submitted to us through our open submission program (we’re proud to be one of the few offices that take unsolicited submissions – even though, admittedly, it can take us a while to get to all of ’em, but if you saw our inbox, you’d understand) as well as through our script coverage service.

And if there’s one commonality between all of the new plays, especially the ones by new-er writers, it’s that most of them are overwritten.

By overwritten, I don’t mean that they’re just long. Because I bet if you polled the most successful playwrights, screenwriters, novelists, speechwriters, etc. about the first drafts of their best work, they’d all say the final draft was shorter (or, as I like to say, more efficient) than their first. So all of us start out with too much, and that’s not necessarily bad. (I often describe the rewriting process like sculpting a statue – you start with a glob of clay . . . you take a little off, then a little more, and then a little more . . . )

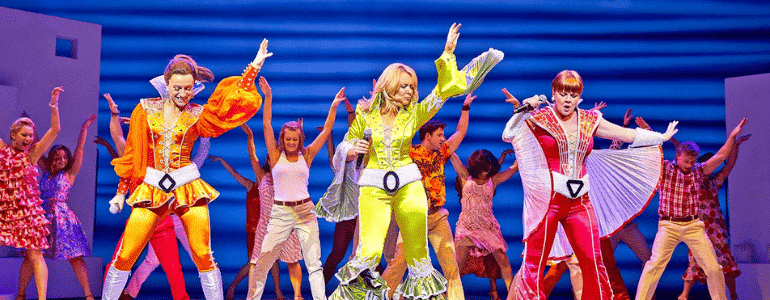

So it’s not long I’m talking about. What I’m talking about is different . . . and it’s specific to writing for the stage or any performance art, as opposed to fiction, poetry, etc.

See, the text you type into your little word processor, or Final Draft if you want to be really cool (I swear by it), wasn’t meant to be read. It was meant to be said.

And I find that one of the simplest mistakes that all writers make is that they forget that great actors don’t need a ton of text to get a certain emotion across. Or, simply said, the words don’t have to do all the work. The inflection, the body language, the movement, and so on can sometimes do so much more than a paragraph of words that try to do the same thing.

Overwriting is an easy trap to fall into, because as Terrence McNally told me in his podcast, writing is the ultimate activity for control freaks. And if you’re a control freak, then you might find yourself writing too much “to make sure that the audience gets it.”

But that’s not necessary. Make sure the director gets it. He or she will make sure the actor gets it. And the audience will not only get it, but they’ll enjoy it that much more.

(This blog-tip was inspired by my Director of Creative Development, Eric Webb, who is the guy who reads all those script submissions. Eric and I are cookin’ up a cool program with more writer tips like this, but we’re not ready to talk about it yet. But if you want to be the first to know, sign up below. It won’t be announced on this blog, so the email below is the only way to get the scoop.)

(Got a comment? I love ‘em, so comment below! Email Subscribers, click here then scroll down to say what’s on your mind!)

– – – – –

FUN STUFF:

– Win an autographed copy of Seth Rudetsky’s The Rise and Fall of a Theater Geek! Click here.

– Listen to Podcast Episode #33 with writer Theresa Rebeck! Click here.

– Follow Spring Awakening‘s journey to opening night! Click here to read The Associate Producer’s Perspective.

Podcasting

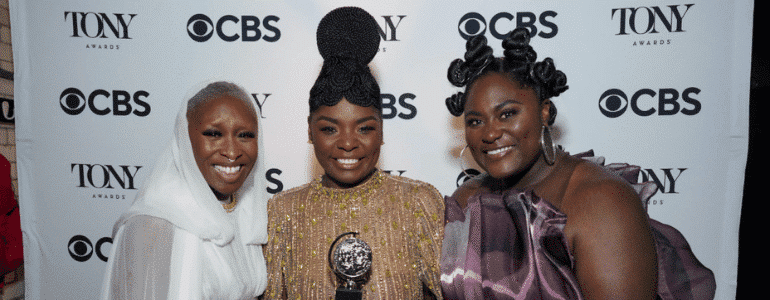

Ken created one of the first Broadway podcasts, recording over 250 episodes over 7 years. It features interviews with A-listers in the theater about how they “made it”, including 2 Pulitzer Prize Winners, 7 Academy Award Winners and 76 Tony Award winners. Notable guests include Pasek & Paul, Kenny Leon, Lynn Ahrens and more.